As a newly minted freshman from a science high school in New York City, I entered Harvard with a tentative plan to study psychology. I had worked in a neuroscience lab for the three previous summers, so applying what I had learned to my concentration seemed to make perfect sense. Though I enjoyed my introductory courses, by second semester I found myself gravitating toward literature and creative-writing classes. Reading was my favorite pastime as a child, and I had always enjoyed the relative peace of an essay compared to the time crunch of an exam. Still, pursuing a concentration where these activities would constitute my assignments had never occurred to me. As sophomore fall and its concentration-declaration date approached, however, I felt myself coming to a revelation I had never expected: I was probably an English concentrator.

I felt a sense of impending doom at this personal discovery. After four years at a scientifically driven institution, the idea of using a degree in the humanities to forge a successful career was new. The short stories and articles I had written in high school always felt too much like fun to constitute serious academic work. Yet as I scrolled through Harvard’s 48 concentrations the summer before my sophomore year, I knew the choice had been made long before I sat longingly reading the syllabi of English classes—with their lists of books I had always wanted to read—instead of those for psychology courses.

Determined to push my doubts away, I set about creating a plan of study. The one major problem that stood between me and happily enrolling in English courses was my uncertainty about which to take first. High-school AP Literature had taught me to identify anaphoras and metonyms, and impressed upon me a profound understanding of the green light in The Great Gatsby, but the wide variety of English offerings felt daunting. Biology concentrators must take Life Sciences 1a to proceed to higher-level classes; computer-science enthusiasts have the fabled CS 50; Ec 10 is a staple of the economics department and anyone considering finance. But with the English department’s array of seminars and lectures that can be taken in any order, where was a budding concentrator to begin?

My sophomore fall, the answer came, luckily, in the form of English 110: “Humanities Colloquium.” Then taught every other year by Cogan University Professor Stephen Greenblatt and Bass professor of English Louis Menand, the syllabus amounted to the closest thing Harvard offers to a “great books” course. We read everything from Aristotle to Austen, leading up to Joyce’s Ulysses. I also enrolled in a history of English literature course, and came out of the semester feeling confident that I had the basic knowledge and credentials to take courses with narrower fields of focus.

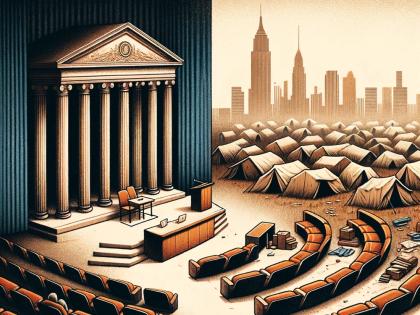

Perhaps not as fortuitous, the “attack” and subsequent “defense” of the humanities began that semester. Articles appeared left and right about how enrollments in humanities concentrations and classes were declining in favor of classes that offered a more secure (and lucrative) career path. An op-ed entitled “Let Them Eat Code” mentioned by several of my professors in a sarcastic yet sad tone, appeared in The Harvard Crimson, declaring that those who pursue the sciences are “not especially sorry to see the English majors go.” This past September, The Yale Daily News published a response to the news that CS 50 is Harvard’s largest course now, and entitled its article “Let Them Eat Humanities.” “While some at Yale have been alarmed by the decline in humanities enrollment,” writes the author, “at Harvard this has been celebrated.”

I wish he had seen the sad look in my professors’ eyes when they cracked feeble jokes about the fact that an editorial itself cannot be written without skills of rhetoric that cannot be taught in any kind of computer-science class, no matter how enticing that field’s tricks, applications, and potentially lucrative careers. We faithful consumers of the humanities, meek eschewers of code, listened and laughed; one editorial written by a small group of people does not represent a definitive trend. But still, it didn’t bode well.

I loudly applaud all those who fight for the humanities, and long to place those who dismiss these fields in a quiet time-out zone, with a only a few good books for entertainment. Still, there is a striking vein of thought that I have noticed in many an impassioned defense of the study of literature. Although the humanities’ champions certainly take care to stress how important the advancement of literature and writing is for our culture and language, there is often an undercurrent of how delightfully applicable studying literature is to a multitude of fields.

A recent Harvard Magazine article (“Toward Cultural Citizenship,” May-June, page 35), quotes Lawrence Bacow, a Harvard Corporation member and former president of Tufts, noting that when corporate executives seek employees, they “look for critical thinkers, candidates with a basic understanding of culture.” The introduction to The Heart of the Matter, a 2013 report by the Academy of Arts and Sciences on the climate of humanities in American education, asks, “Who will lead America into a bright future?” and responds, “Citizens who are educated in the broadest possible sense, so they can participate in their own governance and engage with the world,” specifically citing experts in national security, foreign service, and elected officials. A 2013 report by the Faculty of Arts and Sciences’ arts and humanities division entitled “The Teaching of the Arts and Humanities at Harvard College: Mapping the Future,” compares those who study literature to engineers, noting that “just as the engineer makes life-transforming models through drawing on her ingenum, or imagination, so too the artist, and those emboldened to evaluation through responsiveness to art, imagine the remaking of an always recalcitrant world.”

All these comments analogize pursuing studies in the humanities to preparing for fields that do not specifically engage in literature, such as government or engineering. This is unsurprising, considering the current climate for careers in the humanities. According to a Forbes article published this past January, the National Association of Colleges and Employers reported that although 68.7 percent of computer-science majors received at least one job offer after graduation, only 33 percent of English majors did. Statistics such as these help to explain why reports and critics seeking to convince undergraduates to major in the humanities often argue that the analytical and rhetorical skills they’ll learn will be useful in fields that have lots of jobs available to graduates.

Job prospects aside, I would like to propose that there is something to be said for reading a book simply for the sake of reading a book. Delving into Dante’s Inferno will not advance your career as much as a trip to a consulting fair (though in both cases you may feel like you’ve gone to hell and back), but you will have enjoyed yourself for a few hours, and may find reason to discuss the ideas or language with a friend. I spoke with a few friends who had also taken English 110, and we each seemed to have taken it for the same reason: to be a more interesting, well-read person.

“It’s about having things to talk about,” said Lily Sugrue ’16, a history concentrator. “It’s also one of the few courses at Harvard that actually acknowledges that not everybody comes in with a classical, or with the same, background.” She appreciated the broad Humanities Colloquium approach because “there’s not a book in there that you haven’t heard a reference to in 20 other places in your life.”

“People always talk about Columbia, where they have a core curriculum…I figured that it would be cool to get this solid basis,” said Kiara Barrow, a junior English concentrator who also took the course. “[The colloquium] familiarized me with a lot of things I wouldn’t otherwise be familiar with.” Barrow spoke to the often “diffuse” structure of the English concentration, which does not require students to choose a set of courses focused on particular types of literature, or on literature from specific times and places. “When I tell people from outside Harvard that I’m majoring in English,” she reported, “they usually ask, ‘So, what do you do within that?’” Questions like these stem from the findings in reports like the one conducted by NACE. Specialization, such as the programming experience gained by computer-science majors, or the computing skills taught to accounting majors, is what most often appears to land students jobs upon graduation. The English department does stipulate that students take certain courses (on a foreign literature, for example, or involving Shakespeare), but there are always multiple options within each category, allowing students to follow their interests. This is a more ambiguous approach than that of some science concentrations, but it matches the way people embrace literature: there’s no one way to love, or read, a book.

One of my favorite writers, Oscar Wilde, once noted, “If one cannot enjoy reading a book over and over again, there is no use in reading it at all.” Books that we study in college have been vetted, dissected, critiqued, awarded, and occasionally burned. The one thing they all have in common is that they have been read, and reread, and have messages worthy of passing down from one generation to the next. In the end, what may end up saving the humanities may be their broader applications, such as writing and analytical skills for lawyers, or even the multiple subjects for cocktail conversation that help one get ahead at a fundraiser or networking event. But in the moments when the lawyer, entrepreneur, or consultant is reading, or rereading, a book, I do hope that he or she enjoys the simple act of flipping the pages, enjoys absorbing the story, and enjoys feeling happy, sad, or angry when the tale ends and the trail of ink vanishes into a blank page. I do hope (and fervently), that this particular pleasure is enough.