How does one read a Russian poem? Stephanie Sandler, Monrad professor of Slavic languages and literatures, had one easy answer: read it in Russian.

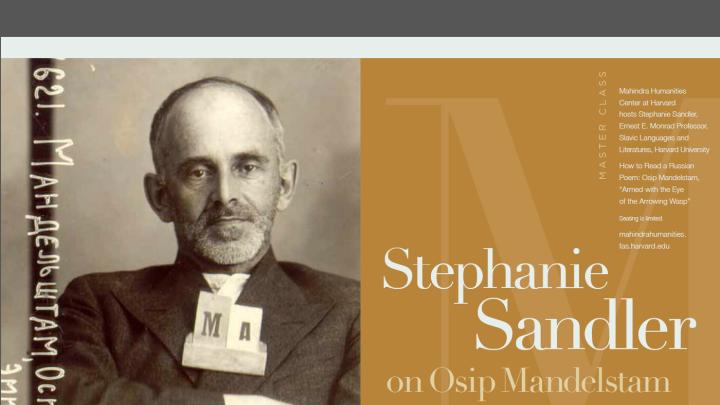

Typically, master classes are led by performers; the Mahindra Humanities Center’s master classes are led by scholars, who for an afternoon hour engage their audiences in the practice of close-reading. Last Tuesday, every seat in the Barker Center classroom was full, each person supplied with a printout of Osip Mandelstam’s “Wasps.” This mixed company required a translation, and the professor had provided two: one by Christian Wiman, from his 2012 collection, Stolen Air; the other, older and more literal, by Clarence Brown and W.S. Merwin.

“There is no way to begin a master class,” she said, “except to confess a certain ambivalence about mastery.” Forced reliance on a translation already confounds readers’ ambitions to immerse themselves in the poetry of another language—but in some sense, Sandler added, all readers are translators, even in their native tongue: we are “carrying over meanings and sound from a poem before us, into the whole archive—of words and phrases, of rhythms and melodies—that fill our heads.”

“Mastery” is a freighted idea for this poem in particular, and for Mandelstam more generally. In 1934, Stalin himself had called up Mandelstam’s friend, the writer Boris Pasternak, in the middle of the night, to ask if Mandelstam was, indeed, a “master.”

“What could he have meant by that?” asked Sandler. At the time, Pasternak did not know how to answer. But Mandelstam himself had come to view the word negatively. “Masters” had merely made themselves useful to the Soviet state as versifiers. Artists with agency—who wrote poems like his own “Stalin Epigram,” likening the Comrade’s fingers to worms—were arrested, exiled, sent to the Gulag. In 1930s Russia, “mastery” was associated with brutal power and coercion. Mandelstam viewed “artistic mastery” with wariness as well as longing.

“Wasps” begins with the image of narrow wasps sucking at the earth’s axis, and declares envy for their cunning, and for their singing. At first, the speaker praises the mind’s power to memorize and gather in sense impressions. Across three stanzas, Sandler said, the poem shifts from the image of the wasps’ piercing sight to expressing a desire to listen. The initial yearning for mastery, for better memorization and more forceful sense impressions, disappears. In its place emerges a yearning for submission, a more capacious ability to hear.

After reading aloud all three versions of the poem, the professor drew attention to the repeated lines and sounds of the original. In Russian, a rhyme-rich language, the word “wasp” is a homonym for the word “axis.” The poem turns on the shared phoneme that brings a buzzing sound to the first lines—“ось,” which echoes the o-sound of the poet’s name, Osip, and also suggests the long “o” in “Joseph Stalin.” Another detail cements the connection: the word Mandelstam uses to describe the wasps, “mighty,” was an almost compulsory epithet for Stalin; the adjective appears in Mandelstam’s ode to the leader, written that same year (and, most scholars believe, under duress). Such “shuttling between sounds and names,” argued Sandler, encourages us to read the poem as a “meditation on the terrible threat of a fated connection.”

To elucidate the poem, she briefly explained a few intricacies of Russian grammar—the conditional voice, the etymological linkages between words. Her talk also brought in sources ranging from other Mandelstam poems to an interview with his widow (which she’d found the week before on YouTube). This gave the audience a sense of what a scholar puts in her toolbox when she goes about opening up a poem and seeing what makes it tick. “Wasps” calls for readers to slow down and listen, Sandler said, and to remember the circumstances under which Mandelstam wrote the poem.

Stalin’s Russia may have been concerned with art’s political import; Sandler’s audience asked different questions about how a poem derives its value. Several centered on Wiman’s translation, variations on a shared concern: his poem uses neologisms and compound words, and inserts images that never appear in the original. “Wasps” might be about submission, but this American poet seemed unconcerned with submitting to Mandelstam, or at least to the rubric of “faithfulness.” Did his version cease to be a translation?

Sandler answered that she thought Wiman’s work had, as a goal, “the original poem as a destination.” Wiman could improvise his own song from the older poet’s materials, while remaining attentive to how his incarnation resonated with the original. Its echoes would lead the reader to its source, to Mandelstam.

The class ended with a challenge from the front of the room: “Is this poem a lesser poem without the biographical reference?” Sandler took a theatrical step back, as if overcome by shock. She launched into a vehement recitation of the poem in the original Russian before stopping and exclaiming, “No way!”

In fact, Sandler said, “You don't need to know anything! You don't need to know anything to be hypnotized by the sound of a poem, and by wanting to know what it means.” As a teacher, she added, she provides context because “we should bring to poetry every molecule of everything that we can. It all should feed our ways of reading the text.” But a poem fails or triumphs on “the way it commands us to return to it”—if only by pure sound alone. With the looping cadences of her declamation still hanging in the air, she could comfortably say: “This poem, I think, has it.”