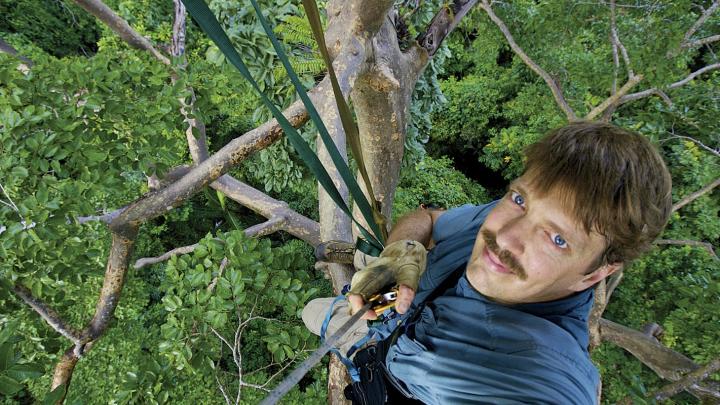

In 2010 biologist and National Geographic photographer Tim Laman, Ph.D. ’94, again found himself more than 80 feet off the ground, hidden in a rainforest blind made of skinny palm trees and leaves woven together with vines. At 4:30 a.m. it was still dark.

He and his research partner, ornithologist Edwin Scholes, had taken 10 different planes and two boats to get to the Aru Islands, between New Guinea and Australia, then hiked a few hours into the forest to create a campsite. It was their fifteenth expedition on an eight-year mission to document all 39 species of the birds-of-paradise in the wild—something never done before.

The palm-tree blind faced a lek, a spot where male birds assemble for competitive mating displays. The blind held not only Laman’s muscular six-foot-four-inch frame, but also his tripod and digital SLR cameras (for close-up stills and video), an audio recorder, and a laptop computer. The last was connected, by a cable he had run across the canopy, to a camouflaged camera that took wide shots by remote control.

At sunrise, two male Greater Birds-of-Paradise arrived. With billowing golden plumage rising above their rust-red wings, they spread their feathers wide and hopped about madly, singing a one-note tune, their yellow-and-iridescent-green heads bobbing for attention. Then each froze, like a runway model jutting out a chiseled jaw, as their less dazzling female counterpart nosed around critically, checking them out. A choice was made and the pair did what they were born to do, then flew away.

As the lone male lingered on the branch, Laman saw his “dream shot” emerge. “He was hanging out with all his plumes spread and the sun came up and illuminated these pale clouds over the mist of the rainforest, casting a yellow light,” he says. “And I got the shot!”

That became the opening spread of Laman and Scholes’s Birds of Paradise, Revealing the World’s Most Extraordinary Birds, published by National Geographic and the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, which together funded most of the pair’s 51 field-research sites in New Guinea and parts of northeastern Australia. The new, coffee-table book features ethereal and intimate images of the birds in all their glory, culled from 39,568 that Laman brought back—from 2,006 hours spent in rainforest blinds—and painstakingly catalogued.

“The book celebrates the beauty and diversity of these birds and the importance of conservation in protecting them,” says Laman, whose doctoral research focused on rainforest ecology. “I’m also excited about the contribution we’ve made to scientific understanding.” Their project offers the most comprehensive look so far at this dynamic avian family. Detailed accounts of habits, habitat, calls, evolutionary history, and singular features are paired with maps of and notes on migration and terrain.

The birds’ unique anatomical features and comparative sexual selection practices are highlighted. The Twelve-Wired Bird-of-Paradise male, for example, uses elongated central shafts of plumage to “tickle” the female; the Superb male transforms into a ghoulish turquoise smiley face by dramatically repositioning his plumage; the Western Parotia male engages in a whirling dance during which its side feathers flare out like a tutu. “The diversity of the forms were extraordinary: the variety of shape, size, feathers, colors, the long tail feathers, and the wires coming out of their heads,” Laman notes. The researchers’ extensive new material, such as documentation of two species’ previously unseen courtship rituals, and 2,256 video and audio recordings, are now archived at the Cornell Lab’s Macaulay Library, where Scholes is the biodiversity video curator. At least six scientific papers outlining their findings are also slated for publication.

Further enlivening the book are histories of earlier explorers—such as Laman’s hero, the nineteenth-century naturalist Alfred Russel Wallace, co-discoverer of natural selection—interspersed with tales of the pair’s own adventures. On one trip, Scholes’s appendix burst at a remote campsite and they spent five days getting him to a hospital. Twice they found themselves adrift at sea in broken-down boats. Not to mention all the other discomforts field biologists endure. “It’s not cool to whine about the bugs,” Laman maintains. “Although the leeches in Borneo are bad.”

All told, Laman has spent five years in Bornean rainforests, on projects including his dissertation on the interactions between strangler fig trees and the wildlife that help disperse their seeds. He often shared the same field station in the Gunung Palung National Park with orangutan expert Cheryl Knott, Ph.D. ’99—now his wife, and an associate professor at Boston University. (The couple and their two children, Russell, 12—named for Wallace—and Jessica, 8, live in Lexington, Massachusetts.) The whole family has traveled many times to Borneo, and will journey to the Galápagos Islands in February. In 2011, Laman took his son to Antarctica for three weeks, prompting Russell to note not long ago that he’d already set foot on every continent except Africa. Yet they are just as thrilled to observe the life of local species. A phoebe nest sits above their front door: the brown-and-white birds migrate from South America and, atypically, have used the same nest for three years. Laman rigged a video camera so that he and his kids “could sit inside and watch the babies being fed and raised,” he explains. Not as exciting as fording rivers and climbing trees in the rainforest, but wondrous just the same.

Laman has always been riveted by the natural world, with all its complex and beautiful forms. Born and raised in Japan, “never far from lakes, mountains, or the ocean,” where his parents were American missionaries, he believes his international upbringing “has probably led me to being comfortable working all over the world. I had no clear career plan: ‘I’m going to get a Ph.D. and then become a professional photographer,’” he adds. “I kind of made it up as I went along.” Two years of a doctoral program in neuroscience and animal behavior at Harvard left him unhappy about spending the rest of his career indoors, so in 1987 he took a year off as a field assistant in Borneo with biologist and ecologist Mark Leighton (then an assistant professor in biological anthropology and now an instructor at the Harvard Extension School).

There, Laman fell in love with the terrain and wildlife. He transferred to the department of organismic and evolutionary biology on his return and completed his doctorate. But along the way, he became frustrated by academic articles that “only reach a handful of scientists,” and wanted a wider audience.

He chose to return to Borneo for postdoctoral research and to focus on his photography, a longtime hobby. His first National Geographic article, published in 1997, covered strangler figs; it was quickly followed by another article, written by Knott, that used his images of orangutans. “I soon became their rainforest guy,” Laman says; by 1999, wildlife photography (supplemented by some science journalism) was his full-time job.

Since then he’s produced 20 feature stories for National Geographic; has worked for other publications, such as his kids’ favorite, Ranger Rick; and has won awards for his images (http://timlaman.com). He’s also a frequent lecturer on environmental education trips. In fact, his first glimpse of a bird-of-paradise came while accompanying a Harvard Museum of Natural History trip to Indonesia in 1990.

It “was just enough to make me eager to go back,” he says. He had read Wallace’s tales of exploration, The Malay Archipelago, before his first trip to Borneo in 1987; one section chronicles the naturalist’s own trip to the Aru Islands more than 150 years ago, where he was the first Westerner to see these “most beautiful and most wonderful” creatures alive in their homeland. Related to crows in structure and habit, these enchanters, Wallace wrote, “are characterised by extraordinary developments of plumage...unequalled in any other family of birds. In several species large tufts of delicate bright-coloured feathers spring from each side of the body beneath the wings, forming trains, or fans, or shields; and the middle feathers of the tail are often elongated into wires, twisted into fantastic shapes, or adorned with the most brilliant metallic tints.” Today, the rural parts of the Aru Islands are largely unchanged since Wallace’s visit, but there are far fewer birds, due to their only consistent enemy: humans.

Laman’s birds-of-paradise odyssey began in 2003, when National Geographic accepted his pitch to do a photo spread on the subject; the birds had not been covered since the 1950s because they are so difficult to find and record. Laman then contacted Scholes, the only active researcher in the field he could find, and thus began a five-trip project from 2004 to 2006 that led to a 2007 article. The subsequent “mission,” Laman recalls, came out of a fateful “semi-delirious camp fire talk in which Ed and I said, ‘Hey, we ought to get all 39 species. It can’t be that hard, we’re already halfway there!’”

Laman sees his project as a modern version of Wallace’s essential work. “If I had lived in his lifetime,” he says, “I might have ended up in a similar line of work—as a roving naturalist.” Wallace was fascinated by exploring foreign lands, “but he also had a high-level scientific inquisitiveness with which he pursued the species question—how many are there and how did they get that way?—that led him to natural selection.

“He was shooting birds and bringing them back for scientists and private collectors,” Laman adds, “and we were shooting video and audio of them so that people 100 years from now can still see how extraordinary these birds were in life. For me, that’s the most exciting thing.”