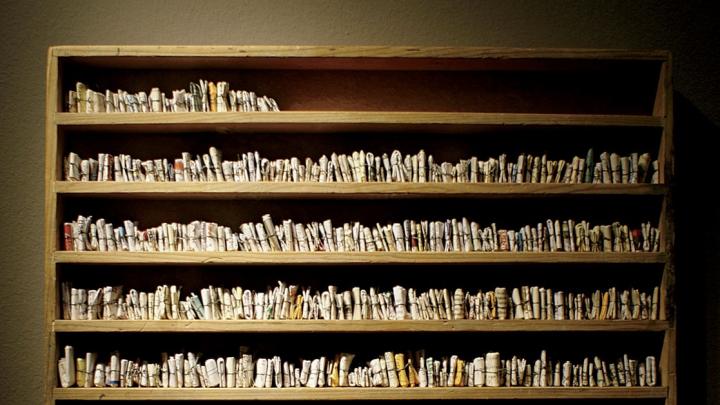

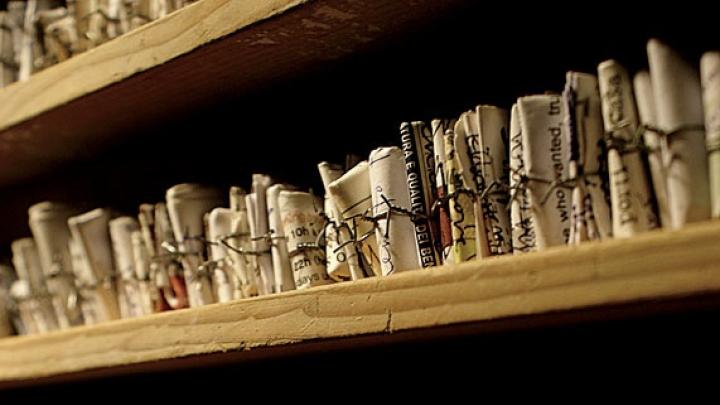

Unspoken, 10.22.10 - 07.07.11 forgoes the traditional mosaic materials of stone and glass. Instead, “It’s a very personal piece speaking of my [verbal] isolation” following a move from New York City to Italy, explains artist Samantha Holmes ’06 on her website (www.samantha-holmes.com). Hundreds of notes she wrote on paper, each folded and tied with wire, rest upon nine shelves in a small wooden cabinet. Holmes knew little Italian then, having just begun graduate study in Ravenna, and the notes capture “thoughts you don’t say aloud—not having the language is only one reason—there’s courtesy, necessity, fear, desire. They are thoughts that were composed but never received; they remain suspended in space between artist and viewer. It’s a strange and uncomfortable experience to have it in the museum, as they are all the thoughts I couldn’t express, and that means they are the most private thoughts I had at that time.”

Unspoken, 10.22.10 - 07.07.11 now belongs to the permanent collection of the Museo d’Arte della Città di Ravenna. The provocative work, whose only resemblance to a traditional mosaic is the assembly of a larger image from smaller pieces, also won the 2011 international GAEM (Giovani Artisti e Mosaico) Prize for experimental mosaic. “It’s important for me to illustrate that mosaic doesn’t have to be just stone and glass and cement,” Holmes says.

She can, however, work in traditional media, and made her most recent piece, Absence, from small fragments—tesserae—of marble and glass, with gold elements. Holmes installed it last October on a brick wall at the ARTPLAY Design Center, an old, now converted, factory building in Moscow. Absence is the converse of a classic mosaic portrait of a saint of the Church: the piece limns the outline of the saint’s body and haloed head—but there is no saint. The brick wall behind is all that appears in the space where we anticipate a sacred figure. “The saint is only a delineated absence,” Holmes says. “The piece asks the viewer to fill it in—according to whatever belief structure they want to use. It evokes the desire we have to fill in that space.”

To fully appreciate Absence, the viewer must see it in the context of the history of mosaic, as the artist did. Mosaic is one of the most ancient art forms, and the permanence of its traditional materials led Renaissance author Giorgio Vasari to call it “painting for eternity.” This is why “mosaics have been used by religions and empires—Christianity, Islam, the Roman Empire, Byzantium—to represent all sorts of belief systems,” Holmes explains. “[The medium] was also picked up by capitalists in New York City, by Fascists in Italy, and by Communists in Russia. Wherever there’s a strong ideology that believes itself permanent, or wants to believe itself permanent, you will see mosaics.

“But we have a society in which those empires have fallen,” she continues, “and we live amid doubt, insecurity, and impermanence. The society around us has turned away from the kind of religion that provided answers to questions of life and death, or gave us the way to live. Instead I ask, in my work, how we can make sense of the world without those ideologies.”

As mosaics are rare in contemporary art, “viewers tend to approach them with the traditional context of mosaic in mind,” Holmes explains. The question of permanence, then, informs Absence, where the space vacated by the saint reveals only a deteriorating brick wall. “There’s a feeling of emptiness and longing,” she notes, “which is related to there being something missing in society to help us answer these questions. What happens to a mosaic when the central figures—the saints and gods—are not there anymore? These are questions for which the medium of mosaic is particularly well suited. Its sense of permanence contrasts directly with the surroundings. The ideal world promised by the church, where there is justice, immortality, and everything happens for a reason, contrasts with the world we actually live in, which is complicated, painful, ultimately given to decline, and holds nothing that is immortal.” For Holmes, traditional mosaic, built from fragments, reflects the “coexistence of acts of creation and destruction”: to make a new work, the artist, using a hammer and chisel, fragments stone into pieces.

Holmes discovered mosaic as a visual and environmental studies concentrator, and won a Michael Christian traveling fellowship to study mosaics in Greece and Italy one summer. She spent a few years at frog design inc. (an international product and digital design firm in New York) before moving to Ravenna to enroll at the Accademia di Belle Arti to learn traditional mosaic techniques. Her Italian is much stronger now, especially for words related to her art, like martellina, a type of hammer specific to mosaic. In fact, she says, “I don’t know the English words for some of the tools we use!”