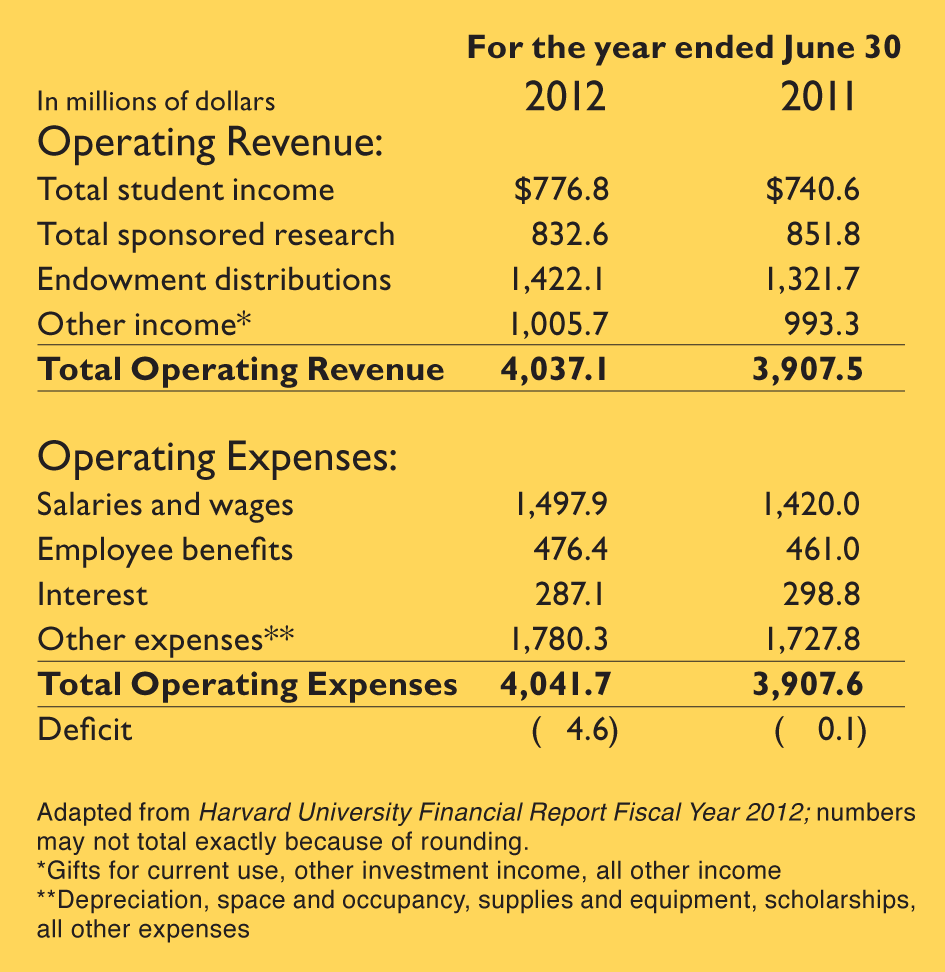

Harvard’s annual financial report for fiscal year 2012 (ended last June 30), released in early November, paints in attention-getting terms a sober portrait of the University’s circumstances today—and likely in the years to come. That context overshadows the latest (nearly break-even) financial results, summarized in the chart and analyzed in full detail at http://harvardmag.com/financial-report.

President Drew Faust’s introduction extolls some achievements of the year—the learning and teaching initiative, edX, and the I-Lab—before pivoting to financial crises in Washington, D.C., and in Europe, and other uncertainties “likely to prove even more destabilizing in the months ahead.” This proves a gentle segue to the castor oil in the blandly titled “Financial Overview” by vice president for finance Daniel S. Shore, Harvard’s chief financial officer, and Corporation member James F. Rothenberg, University treasurer since 2004.

Revenue increased $130 million, to just over $4.0 billion—but expenses increased a few million dollars more (also to more than $4.0 billion), yielding a negligible $4.5-million operating deficit. Endowment distributions for operations drove revenue growth in fiscal 2012. Student income increased about 5 percent, to just above three-quarters of a billion dollars (after $357 million in financial aid is subtracted from tuition and fee revenue). But sponsored research support declined. Increased expenses reflected higher compensation—the people costs that account for nearly half Harvard’s annual spending. Interest expense declined; in fiscal 2012, the University redeemed about $300 million of outstanding debt.

A fiscal roller-coaster ride. “Since Harvard thinks and acts in long-term timeframes,” Shore and Rothenberg write, “we believe it is important” to consider fiscal 2012 “in the broader context of Harvard’s changed financial circumstances and prospects.” Beginning in 2002, “the University enjoyed substantial growth through fiscal 2008 driven by large increases in both net assets and debt”; a chart accompanying their text demonstrates that as the endowment more than doubled (to $37 billion), so did borrowings (to nearly $4 billion). Faculty ranks expanded 10 percent. Campus facilities were enlarged by more than four million square feet (20 percent), heavily funded with debt—and all entailing expenses for operations and maintenance. The financial-aid budget boomed.

Then, they continue, “The global financial crisis changed the University’s financial profile in a sudden and consequential way.” The endowment lost $11 billion in value. Harvard incurred $3 billion in additional losses on various financial and investment transactions, and had to take on additional debt. Interest costs doubled, to nearly $300 million from fiscal 2008 to fiscal 2011, as endowment funds for operations—the schools’ largest source of revenue—suddenly declined. Worsening matters, “over the past 10 years the University experienced only minimal inflation-adjusted growth in key non-endowment sources of revenue.” For instance, increased financial-aid spending has meant that “undergraduate net tuition actually has declined on an inflation-adjusted basis during the past decade at an average rate of 5 percent.” Excluding the national economic-stimulus program, “federal sponsored research revenue has had an inflation-adjusted compound annual growth rate of only 2 percent since 2002, and non-federal sponsored research has fared worse. Meanwhile…benefits expense has more than doubled in the past decade to $476 million in fiscal 2012.”

The near-term response has been retrenchment: tighter staffing and attempts to rationalize information technology, purchasing, and the decentralized libraries structure. But Shore and Rothenberg call that merely a prologue to “an even more fundamental examination of our activities with the goal of more crisply prioritizing what we do and what we are willing to forgo.”

The future. Sketching the need for a new economic model for Harvard and other private research universities, they observe:

We are challenged by volatility in the capital markets due to our endowment dependence and disproportionately fixed cost structure. We depend considerably on [federal] funding of biomedical research at a time when the government’s projected deficits and accumulated debt create enormous pressure to reduce such discretionary dollars. The University’s sizable campus requires significant annual funding to maintain and still more funding to address deferred maintenance.

Turning to matters at hand, they term the increase in employee-benefit costs “unsupportable…relative to actual and expected growth” in revenue. Harvard is now addressing those costs largely by effecting changes in healthcare benefits (co-insurance and deductibles rose during calendar 2012), and by increasing the share of premiums borne by higher-paid employees in calendar 2013.

In a sign of the rising pressures, disagreements about compensation and healthcare costs have caused a public, contentious breach with the Harvard Union of Clerical and Technical Workers, the University’s largest union; at press time, the parties had not negotiated a successor to the contract that expired last June 30. Academically, increased distributions from the endowment were the largest source of additional operating revenue in fiscal 2012 (after two years of reduced distributions). For fiscal 2013, the Corporation approved a further 5 percent increase, but it now uses a multiyear smoothing formula to set future distributions. The endowment recovered robustly in fiscal 2010 and 2011, but its value declined in fiscal 2012 (reflecting a slightly negative investment return and spending during the year). So in guidance for fiscal 2014 budgets, the Corporation has approved only a 2 percent increase in the distribution—and that subject to revision if there is “severe market dislocation.”

Foreseeing a lasting shift from “many decades of growth and stability” to “rapid, disorienting change” buffeting higher education, the two men restate the case for “integration opportunities” (further wringing out costs through the library reorganization, centralizing information technology, and other initiatives); attack “generous employee benefit offerings”; and urge “exploring incremental revenue” (including “more creative strategies to leverage the University’s space and its vast intellectual resources for additional monies that can be reinvested in our teaching and research aspirations”). And, of course, “a fundraising campaign” (see “The Coming Campaign”).

Despite initial fundraising progress, they view Harvard’s long history and traditions in a decidedly cautionary spirit:

The need for change in higher education is clear given the emerging disconnect between ever-increasing aspirations and universities’ ability to generate the new resources to finance them. Certain aspirations more closely resemble imperatives and will require universities to make decisive and inevitably difficult choices from among competing priorities. We can be successful if we equate change with the opportunity to improve and move forward.

…Success will require a tolerance for ambiguity, an openness to different ways of doing things, a commitment to experimentation, an underlying confidence in our ability to implement a sustainable economic model, and an abiding passion for the University and its impact in the world. These are the same success factors that have enabled Harvard to thrive throughout the centuries, and we expect to achieve similar results in the future.