There’s a kit of items—tape measure, flashlight, camera, and a UV light—Brooke Lampley ’02 takes along to appraise a work of art. “If anything fluoresces under the UV, that indicates that it was added more recently, and the painting may have been retouched,” she says. “Sometimes a work has been damaged—maybe the original surface was cracking—and the damage filled in or covered up.” Lampley is a senior vice president and head of the impressionist and modern art department in the Americas for Christie’s. She travels well over 100,000 air miles a year to see sellers, buyers, and lots of art.

With 53 offices in 32 countries, Christie’s, founded in 1766, is one of the world’s two great auction houses (Sotheby’s is the other half of the duopoly) dealing in art objects—and even extreme-high-end real estate: properties that might also qualify as artworks. Lampley organizes the firm’s biannual evening sales in New York; each typically auctions $200 million worth of art, though the take has gone as high as $500 million. She works on marketing plans, sales strategies, pursuit of consignments, and promotion of sales, while managing a team of 15 in her department. Like Lampley, her team travels widely seeking special pieces because, as she says, “The quality of the art is what powers the most interesting auctions and brings buyers to us.”

Authentication is crucial: for example, Christie’s will not sell a work by the French dadaist Francis Picabia (1879-1953) without a certificate from the Comité Picabia. Experienced intuition also plays a big role. “Ninety-five percent of the time,” Lampley says, “I am looking at something and I am resoundingly sure that it is authentic or inauthentic.”

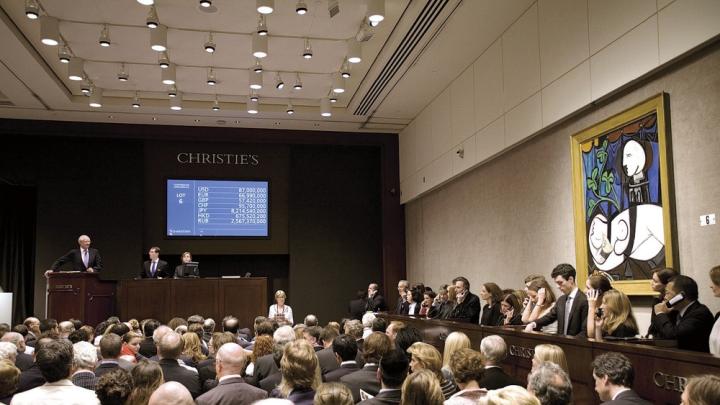

An auction at Christie’s New York headquarters, like this spring’s sale of postwar and contemporary art, gallops along at a bracing clip: the gavel bangs down on most lots in only a minute or two, and some auctions are over in seconds. The auctioneer stands at a lectern atop a podium before the room of bidders and curious spectators. A video screen on the left displays the catalog lot number with a color photograph of the work on offer, while another, to the right, shows the current bid price in seven currencies.

Many of the most active bidders aren’t in the room, or even on the continent. Long wooden counters on both sides accommodate a score of in-house specialists who bid on behalf of clients connected by telephone. Newer art markets like Brazil, China, Russia, and the Middle East “are having a phenomenal impact,” Lampley explains. “Some emerging-market buyers have such deep pockets that they can bid in one sale and completely distort the impressions of the marketplace. Sale statistics might say there were ‘30 percent Russian buyers’—but that could be just one person! An artist’s world record might be tripled at one sale.” That creates a conundrum for those in the art market who must then estimate a price point for the artist’s next sale, given the wide gap between the previous record and the new one.

In meeting such challenges, Lampley draws on a deep background in art history. Born in Manhattan, the daughter of painter Joanne and sportscaster Jim Lampley (now of HBO; the couple is long divorced), she grew up a “very bookish, academic” type who haunted museums; at 14, at the American School in London, she discovered art history, an ideal fusion of her two passions. “I’m inclined toward specificity,” she says, “drilling down deeper and deeper into one thing.” At Harvard, she concentrated in literature and history of art and served as arts editor and president of the Advocate and an officer at the Signet Society. She also worked as a curatorial assistant for the Fogg Art Museum and then, for a postgraduate year, at the Smithsonian’s Hirschhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden. After a year in a Yale doctoral program in art history, Lampley departed with a master’s: “I craved more direct work experience before making a long-term commitment for my career.” Curatorial work at the National Gallery of Art followed. She joined Christie’s in 2004. “It was the first time I had considered the commercial art world—I’d been disdainful of it,” she says. “But I was looking for more diversity in my professional experience, and I think now that Christie’s and Sotheby’s give you the best possible education in connoisseurship—you see such a wide variety of work.”

Rarely, however, does one see an item like the Nature morte (1927) by French painter Fernand Léger (1881-1955) that a Cambridge couple had inherited. They learned that Lampley was a Harvard alumna and contacted her. “It was not in the catalogue raisonné for Fernand Léger, which is unusual, and there is no expert we consult on Léger, so we have to be extremely confident in the authenticity of the work and the provenance,” she says. The painting “was stupendous to look at; it clearly appeared genuine: very graphic, great color, and it represented a type of work that hadn’t come to market for some time. The clients felt strongly that they wanted to set the reserve price at $3.5 million; we agreed to an auction estimate of $3.5 million to $6.5 million, very ambitious for a work of this type. There was a lining on the reverse of the canvas, and I told the client I expected that when we took the lining off, there would be a signature, date, and title of the work inscribed there, because that is what Léger commonly did. We found exactly what we expected to.”

The piece ultimately sold for a $7.2 million hammer price (the “gavel” price, before ancillary fees) to the Nahmad family, well-known art dealers based in Monaco. “A member of the family told the Financial Times they had bought it for their personal collection, as opposed to stock, and described it as of museum quality,” Lampley reports. “It was a remarkable privilege to bring to market a rediscovered masterpiece that had never before been seen and had been in the family’s hands since it was acquired from the artist.”