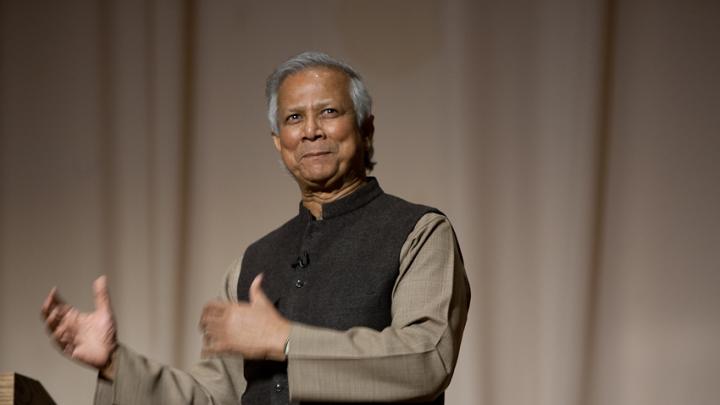

All human beings are endowed with entrepreneurial spirit, “with no exception whatsoever,” microfinance pioneer Muhammad Yunus told listeners at Harvard Business School (HBS) yesterday: some people simply never discover that proclivity because their surroundings do not allow it to blossom.

Before he founded the bank that convinced the world that small loans to the very poor could make a difference—that these people weren’t so grave a repayment risk that loaning to them was foolish—the 2006 Nobel Peace Prize winner was a young professor of economics at Chittagong University, quite proud of the “beautiful, elegant” economic theories he taught. “Then came the famine” of 1974.

He recalled feeling that the theories were “useless” in the face of such suffering. The university where he taught was not in a major urban center, but rather, in a smaller city closer to rural village life, and he traveled to the villages frequently, trying to understand how to alleviate rural poverty. As these visits added up, one phenomenon stood out in his mind: he was troubled by the loan sharking people described. He started keeping track, and counted 42 people he had met who complained of harassment by debt collectors. In total, their debt amounted to $27. This was his epiphany: “I couldn’t believe that people had to suffer so much for so little.”

Although Yunus knew he couldn’t eliminate poverty, he knew he could solve the immediate problem for those 42 people. With $27 of his own money, he paid off their debts. Villagers were shocked that he would do this, he recalled—and banks, too, were astonished when he suggested that this could be done on a larger scale: “They kept repeating for me that it’s impossible to do it.”

By the time he founded Grameen Bank (the name, a Bengali-English hybrid, means “village bank”) in 1983, Yunus had already arranged loans for 28,000 people, using funds from loans he had secured from the government and other banks. To date, Grameen has loaned several billion dollars to millions of borrowers. It has a staff of 25,000 and operates in every single village in Bangladesh, Yunus said.

In his talk, Yunus explained many ways in which he had bucked conventional wisdom. For instance, he never believed that vocational training was necessary to help the poor start businesses; many of them already have in mind a good they could sell or a service they could provide, and just need the capital to buy the first batch of food for a roadside stand or the sewing machine for a tailor shop. “Just give them the money,” Yunus said, “and they figure it out.”

He said his business model has been to look to conventional banks and then “do the opposite”: “They go to the rich; I go to the poor. They go to the men; I go to women. They go to urban centers; I go to the village.” Grameen Bank’s loans require no collateral, charge no interest, and have no repayment date, so recipients can never be in default. The main incentives are that groups of villagers borrow together and act as co-guarantors, and a recipient who repays her loan qualifies for another, larger one. “Conventional banks are owned by rich people,” he said. “We reversed that, too. Ninety-seven percent of shares of Grameen Bank are owned by the borrowers themselves.”

He described several related but separate Grameen initiatives: the sale of low-cost solar-power systems to bring electricity to more than a million homes in Bangladesh so far; a partnership with the French Groupe Danone to distribute low-cost, fortified yogurt to mitigate the malnutrition from which nearly half of Bangladeshi children suffer; and the development, with Adidas, of shoes that can be sold at a price of just one euro. Noting that going barefoot isn’t merely uncomfortable, it’s a health risk, Yunus said it was important to him that Adidas actually find a way to produce the shoes for less than a euro—a more sustainable strategy than developing a product that costs 5 euros and subsidizing the difference—and that the shoes bear the Adidas logo as a symbol that the company stands by its product.

He made no reference to the controversies of the past few years. In 2010, it came to light that some microlenders—notably, SKS Microfinance, India’s largest microcredit firm—were yielding substantial profits for executives and shareholders; elsewhere, some microloan recipients complained they were being harassed and even assaulted to compel repayment.

In 2011, Yunus was removed from his post as managing director of Grameen Bank; his dismissal was upheld by Bangladesh’s high court. The reasons for the dismissal are murky. In a February interview with The New York Times, Yunus called the dismissal “painful” and said, “It makes no sense. There is no meaning to it.”

He noted that the media have speculated that the Bangladeshi prime minister, Sheikh Hasina, requested his removal because she views him as a political rival. (Yunus formed a political party called Nagorik Shakti, Citizens’ Power, in 2007. He told the Times he did this because there was a “political vacuum” in the country at the time and he was being pressured by others to step in, but he soon thought better of it and abandoned the idea.) In the Times interview, Yunus noted that Hasina has never publicly expressed an opinion on his foray into politics.

Yunus took no questions at HBS, and the closest he came to mentioning any of this in his 45-minute speech was to say that he saw the address as an opportunity “to explain and defend myself [and] what I do.” He clarified that he personally does not own a single share in any of the Grameen companies.

Perhaps alluding to microfinance’s tarnished reputation, Yunus said human creative energy had been channeled in the wrong direction: toward making money, rather than solving the world’s problems.

“Human creativity has no limit,” he said. “It’s only a question of how we apply it.”