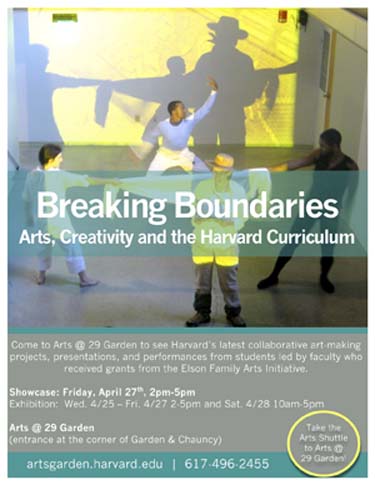

Arts First, a multiday festival of student performances and artworks, taking place this year on April 26-29, has traditionally highlighted the array of extracurricular enterprises that enliven the school year. But significantly, the 2012 celebration features an event, deemed “Breaking Boundaries: Creativity and the Harvard Curriculum,” focused on art-making within undergraduate courses: a small, but long-sought, step toward embedding such activity in students’ Harvard education. The presentations at the Arts @ 29 Garden venue, scheduled from 2 to 5 P.M. on Friday, April 27 (complementing an exhibition running April 25-28), will showcase interdisciplinary coursework, performances, and art works from freshman seminars and General Education courses (with the students and faculty members present), including:

- performances from Music 159, “Analysis: South Indian Music, Theory, Practice,” taught by professor of music Richard Wolf;

- short films from Organismic and Evolutionary Biology 52, “Biology of Plants,” taught by Bullard professor of forestry N. Michele Holbrook and professor of organismic and evolutionary biology Elena Kramer;

- dance and spoken-word poetry performances from “The Choreography and Design of Partnership and Collaboration: Tools, Synthesis, Action,” taught by visiting choreographer Liz Lerman;

- examples of calligraphy from Culture and Belief 12 (a General Education course), “For the Love of God and His Prophet: Religion, Literature, and the Arts in Muslim Cultures,” taught by professor of Indo-Muslim and Islamic religion and cultures Ali Asani, chair of the department of Near Eastern languages and civilizations;

- photography portfolios from Culture and Belief 30, “Photography and Society,” taught by Burden professor of photography Robin Kelsey—profiled in this 2009 Harvard Magazine feature—who is also director of graduate studies for the history of art and architecture department and chair of the Harvard University Committee on the Arts (HUCA);

- and a rotating roster of films and videos, engineering designs and drawing, works in clay, sacred-music performances, Ciceronian oratory, MP3 recordings, and more.

The Context for Creativity

Beyond the faculty members and students immediately involved, this upwelling of art-making reflects a collaboration among three people:

- Diana Sorensen, dean of arts and humanities within the Faculty of Arts and Sciences, and Rothenberg professor of Romance languages and literatures and comparative literature;

- Kelsey, whose committee is charged with advising on the implementation of the 2008 report of the Task Force on the Arts; and

- Louis G. Elson ’85, co-founder and managing partner of Palamon Capital Partners, a London-based private-equity firm, whose philanthropic support has underwritten the Elson Family Arts Initiative—five years of funding that enables Sorensen to solicit grant proposals to seed arts-making ventures throughout a wide variety of courses.

All three expect to attend the April 27 studio event. (Text continues below poster.)

The 2008 task force report remains the fundamental plan for enhancing Harvard’s engagement with arts, creativity, and performance. Its statement of the intellectual case for art-making remains vivid:

To allow innovation and imagination to thrive on our campus, to educate and empower creative minds across all disciplines, to help shape the twenty-first century, Harvard must make the arts an integral part of the cognitive life of the university: for along with the sciences and the humanities, the arts—as they are both experienced and practiced—are irreplaceable instruments of knowledge...Art-making is an expressive practice: it nurtures intense alertness to the intellectual and emotional resources of the human means of communication, in all their complexity. It requires both acute observation and critical self-reflection.

But of course the recommendations—for new programs, degrees, and facilities— unfortunately arrived at the height of the financial crisis and recession, and now presumably await a University capital campaign for execution. It is notable that in their current and recently completed capital campaigns, Princeton and Stanford, respectively, emphasized a new arts district and an entire set of arts buildings (with the accompanying staff and programs). And a report on “Art-Making and the Arts in Research Universities”—just released by a group of academic leaders convened by the University of Michigan as the ArtsEngine initiative—concludes that, among other advantages, “artists benefit research in other disciplines” in the following ways:

- Through data visualization and translation.

- With new ways of conceptualizing questions and information, from the beginning of the process.

- By providing different strategies and expertise for working through problems.

- By spurring technological innovation through the demands of their own creative vision.

- By improving future research capacity through improved retention of at-risk students, and students from diverse backgrounds.

During a recent conversation in his office at the Sackler Museum, Kelsey said his committee, which exists to advise the president and provost on ways to promote art-making and to implement the 2008 recommendations, has neither a staff nor a budget. The members have found it valuable to convene to share ideas, he said, and have helped advance capital-campaign planning for the arts. But they have become directly engaged in a hands-on way of advancing the cause now: through Dean Sorensen and the Elson Family initiative. As Sorensen initially solicited proposals from faculty members, and then began receiving them as word about the program spread, HUCA members have vetted the requests and made recommendations, on the basis of which Sorensen has then made grants—about 10 per semester. Her aim is to incorporate art-making in classes outside the studio offerings of the visual and environmental studies (VES) department. (An exhibition of seven seniors' VES thesis projects—in painting, drawing, video, and installation works, is at the Carpenter Center main gallery and Sert Gallery space, April 27-May 24.)

In his own General Education course on the history of photography, for instance, students have an option to do a photography project in place of a research paper, Kelsey said; the Elson funds have allowed him to bring in two local practitioners to work with the students, who have, in turn, produced stunning portfolios like a bound book of winter images in New Hampshire’s harsh White Mountains.

The work, he hastens to emphasize, is not student amateurism; it is about “finding ways to make art-making an intellectual inquiry.” The students who pursue a photography project must also write about the process and put it into historical perspective. The results, he said, enable him to see clearly what students have come to understand about the history of the medium from engaging with the course content.

Sorensen, in a separate conversation, said her goal in supporting such work (typically through $5,000 instructional grants for a semester course) was exploring art and art-making as “cognitively exciting—as core to the academic work” being done. She cited examples from inserting music-making into a course on the physics of music, or hiring an artist to teach students how to illuminate manuscripts for a course analyzing such works from the medieval era. Unlike a VES course in, say, drawing or painting, she said, “I have not focused on the performance results. I’ve focused on innovating and risk-taking.”

Venture Capital for Artistic Creativity

That approach accords closely with his family’s aim in underwriting art-making at Harvard by providing a sort of “venture funding,” Louis Elson said in a telephone conversation from London.

He noted that his wife, Sarah Elson, an art historian who studied at Princeton and Columbia, had become involved in contemporary art—particularly works that viewers found it challenging to understand and appreciate. To break that barrier, to create “engagement with aggressive, difficult art,” Louis said, Sarah found it productive to emphasize, “There’s a person inside that piece, expressing himself” through that work of art. Connecting oneself to a recalcitrant art object, in other words, becomes an exercise in understanding “why that art was made at that place at that time by that person, for what purpose.” From there, it is a closely related step to thinking about “art-making as an important part of developing that understanding.”

When they sought to become engaged with art-making at Harvard, Louis said, the Elsons were initially interested in the study centers being created in the renovated Fogg Art Museum. But when they were introduced to nascent efforts to promote “active engagement” of students with art-making, Sorensen’s curricular goals immediately resonated. By doubling her request, he said, the Elsons could seed a broad array of arts innovations; provide some tangible, external validation for the initiative; and support ways of displaying the results to the community and conferring recognition on the students and faculty members involved—at the April 27 Arts First exhibition, for instance.

Underwriting the instructional grants for five years, he said, should yield a sufficiently broad array of experiences, over a sufficiently long time, to help inform the University’s decisions on implementing the 2008 task-force recommendations as it builds specific arts-related elements into the plan for the capital campaign. During those five years (this is the third), he said, professors and administrators have “had enough runway to make something happen and see it go” and are now in a position to “improve the reach and efficiency” of curricular art-making in ways that will really affect students’ Harvard experience. “Part of the genius of the program,” he said, “is that it is not course-specific,” in that the funding applies in any course, regardless of subject or title, where a professor conceives a way of using art-making to broaden and deepen students’ access to and involvement with a subject.

As a venture capitalist considering any possible investment, Elson said, “You do need to get it going, get into that experimental phase, let the activity set sort itself out”—just what teachers have been doing as they teach through art-making, and as students engage with their courses in new ways. The results, he said, will extend from appreciating art to art-making to “students’ perceptions of culture and their place in it.”

Although he and Sarah have not yet seen the fruits of the course work, Elson said, students with whom he has spoken about their art-making have told him “it has really gotten under their skin and into their heads. It’s really captivated their imagination.”

In Dean Sorensen’s view, when she, fellow professors, students, the Elsons, and others convene April 27 at “Breaking Boundaries” on Garden Street, they will all see “the transformative effect that art-making has had on the curriculum and students’ work”—the venture-funded sprouts of what they hope will become a much greater University investment in art-making, performance, and creative work in the Harvard of the future.