Joachim Cohen would love to have the product he helped design this summer—a red-balloon faucet fitting called a “Tapminder” that inflates to remind users to conserve water—show up in millions of kitchen sinks one day. But even if that doesn’t happen, the challenge of combining engineering and art to put a new spin on something as universal as water—the focus of the 2011 one-night fall exhibition held by the Laboratory at Harvard, which encourages mixing art and science for innovative solutions—gave Cohen real insight into how to craft a groundbreaking idea.

“Many countries have this false image that water is an unlimited resource, when in developing nations obtaining safe water is a major issue,” said Cohen, standing alongside Tapminder prototypes at the laboratory’s gala exhibition last Friday night. “You put our device on your faucet and as you turn on the water, the balloon grows. Eventually it gets bigger and could explode…and no one wants to get all wet! It helps you stay aware of water-related issues around the globe.”

The exhibition featured projects created by 20 students enrolled in a Harvard School of Engineering and Applied Sciences course called “How to Create Things and Have Them Matter” (ES20). The SEAS students, in collaboration with student groups from other “ArtScience” labs in Cape Town and Paris, spent all summer on this year’s course theme, “The future of water”—brainstorming cutting-edge ideas that involved equal parts science and creativity.

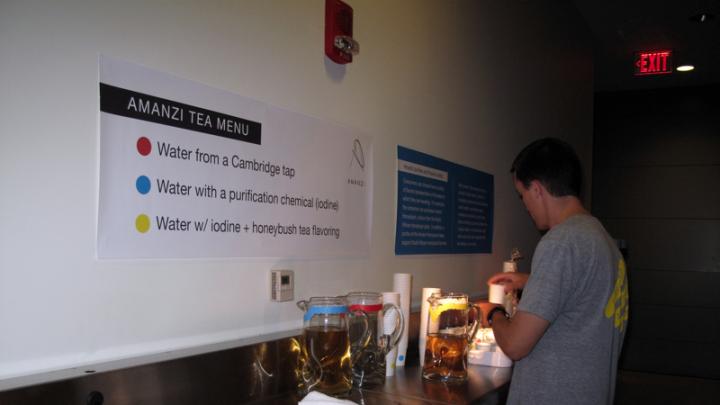

A few feet from “Tapminder” was “Project Ark,” an inflatable lifeboat that provides transportation, drinking water, and shelter to flood victims; other students created “BLUE,” an engineering fashion company focused on social and ecological issues that had donated 10 percent of its equity to a foundation that builds wells for communities that need clean water. “Amanzi” focused on creating jobs for small growers of honeybush tea in South Africa by incorporating their tea into a water-purification system that campers and hikers can use to improve the taste of iodine-treated trail water.

Another group, “UseLESS,” created a plastic bag that can dissolve into soap or laundry detergent. “Our project was driven by the fact that plastic has a bunch of negative effects on the environment and takes hundreds of years to break down,” said senior Talal Alhammad, who took ES20 last spring. “We wanted to find a cool, artistic way to really change it up. We created these bags that have an artistic edge to them but also have positive impacts on the environment.”

All told, 11 student projects were on display in the chicly decorated basement of 52 Oxford Street, which—packed with hundreds of well-dressed attendees—took on the look and feel of an art gallery on opening night. Students carrying trays of paper cups containing tea samples worked the crowd; bathroom users found “Tapminders” on the faucets; and on a large screen, South African artist William Kentridge’s short film The Refusal of Time—imagine a David Lynch movie about Albert Einstein—mesmerized the crowd.

If history holds true, some projects may, in fact, go on to real-world success. Students who created a breathable chocolate spray for a recent exhibition have since launched their own company, selling 400,000 units last year; a soccer ball that creates energy is being marketed to African areas without electricity; and the iPhone app MuseTrek is already in use at the Louvre.

But the success of any one idea is merely bonus on top of the education that students are getting in the class, said McKay professor of the practice of biomedical engineering David Edwards, the lab’s faculty director. “The process is fun and frustrating, and almost none of the signs that exist in a classical education to tell us we are ‘progressing well’ are to be seen,” he explained. “This process of innovation unites innovators of all kinds: artists, scientists, everyone who creates. Students start to learn this in the Lab.”