Not every novelist can say she owes her career to the Nigerian secret police, but the Pulitzer Prize-winning Australian writer Geraldine Brooks, RI ’06, likes to give credit where credit is due. While investigating Shell Oil malfeasance in the Niger Delta as a foreign correspondent for the Wall Street Journal, Brooks ended up on the wrong side of Sani Abacha’s military regime. “To cut a long story short, they didn’t like reporters looking into that, and they threw me in the slammer in Port Harcourt,” she says. Her first reaction wasn’t fear of prison but of her biological clock: “I thought, ‘Oh, gee, if they keep me for too long I’ll be too old to get pregnant,’” Brooks recalls, explaining her decision to trade journalism for the relatively risk-free world of fiction.

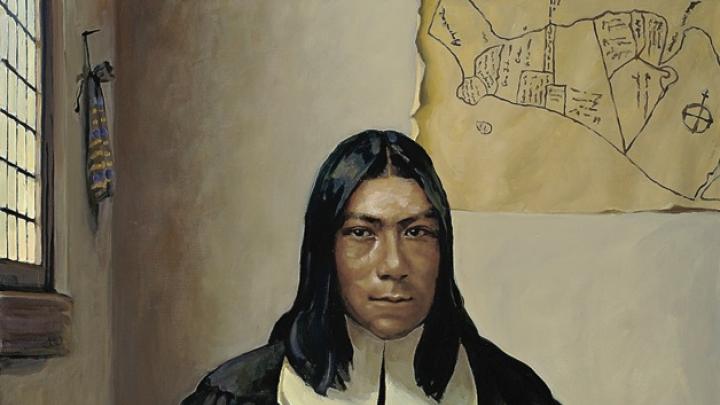

These days, now a mother of two, she works from the quiet of her home on Martha’s Vineyard—the source of inspiration for her newest book. Caleb’s Crossing, appearing this May, tells the story of Caleb Cheeshahteaumauk, a member of the Vineyard’s Wampanoag tribe, whom Brooks first discovered on a map marking the birthplace of Harvard’s first Native American graduate. “I thought it would be really interesting to talk to him about that experience, because I was thinking civil-rights era, maybe 1965, kind of vintage-y,” Brooks recalls. “And then I learned it was 1665 and that was an incredible sort of mind-shift experience…I started to wonder about Harvard and what it was like in the seventeenth century. ”

It’s those austere beginnings that Caleb’s Crossing endeavors to recreate as it covers Cheeshahteaumauk’s journey from the Vineyard wilderness to the rigid world of English Puritanism. Narrated by Bethia Mayfield—a precocious minister’s daughter whose frustrations with Puritan life find an outlet in Caleb—the novel unearths a little-known chapter of Harvard history: the establishment of an Indian College, funded by idealistic missionaries (who aimed to expand the reach of their faith among Native Americans) and abetted by administrators (who hoped to milk the missionaries for funds during Harvard’s leaner years; Brooks quotes then-president Charles Chauncey lamenting “the loud groans of the sinking college”). Harvard’s 1650 charter specifies that the College’s purpose was to provide for “the education of the English and Indian youth of this country, in knowledge and godliness.” (Alas, with the escalation of hostilities between the Wampanoags and the English settlers in King Philip’s War of 1675-76, this aspect of Harvard’s founding mission all but disappeared.)

The Harvard of 1661 is as alien to Caleb, newly arrived in Cambridge, as it would doubtless be to recent graduates accustomed to luxurious dining halls and manicured athletic fields. Bethia vividly describes the down-at-the-heels institution: “I had heard that some had deemed the college building too gorgeous for a wilderness. But the grace of its design cannot have been matched by skill in its construction, for its shingle roof sagged woefully in several places and the sills showed signs of well-advanced rot.” The young scholars, only a handful per class, survive on carefully rationed meals, sometimes even paying their tuition with an all-too-rare side of beef. “I was laughing because everybody was up in arms about not getting a hot breakfast,” Brooks jokes, referring to the 2009 scandale in which Harvard’s dining-hall cutbacks made the New York Times. “I was like—hot breakfast?!”

Like her previous works (Year of Wonders, People of the Book, and the Pulitzer-winning March), Caleb’s Crossing borrows liberally from the historical record. Brooks has a journalist’s zeal for fact-finding, but tries not to let her reportorial impulses overtake the imaginative work. “I like to let the story tell me what I need to know. I love libraries and archives but I try not to get carried away to the point where some fantastic bit of research I stumbled on is going to shape the plot rather than vice versa.”

Because very few letters and diaries from seventeenth-century American women survive, the process of conjuring the narrator’s voice became one of the pleasures and challenges of Caleb’s Crossing. Whereas Caleb, his friend Joel Iacoonis—who would have been a fellow Indian graduate had he not been murdered by seafaring marauders on the way to Commencement—and even Bethia’s family are drawn from real-life figures, Bethia herself is wholly fictional. “It was intriguing to take the scant evidence and try to build a portrait of somebody who is plausible,” Brooks explains. Still, the depth of her research is more than evident: Bethia’s musings take her on detours into everything from the grammar of the Wampanoag language to the dangers of colonial midwifery.

Fittingly, Brooks began researching the novel while a fellow at the Radcliffe Institute. Although she found few remaining traces of seventeenth-century Cambridge to inspire her, Harvard archaeologists have since excavated part of the foundation of the Indian College in the Yard, near present-day Matthews Hall (see “Pay Dirt in Yard Dig,” July-August 2008, page 80). Brooks’s excitement about recovering this lost part of history is palpable: “My dream is, they find a shard of pewter with CC carved in the bottom of it.”