The mayor of Braddock, Pennsylvania, John Fetterman, M.P.P. ’99, trudges around this decimated steel-mill town—with its vacant buildings and grimy air—in size 13 high-tops and gas-station-style work shirts, carrying the weight of a restless but resolute energy. He frowns a lot. Never does he crack that politician’s “meet and greet” smile. Nor does he particularly go out of his way to solicit attention, although with a shaved head and six-foot-eight linebacker frame, he is hard to miss. “My looks worked against me at first,” he says, “because people thought I was a skinhead.”

Fetterman is an outlier in an outlying town. He is a white man with an Ivy League degree and some family money who spent his twenties in existential wanderings—following interests in social work, business, and public policy. But about seven years ago he chose to put down adult roots in this bombed-out historic town on the Monongahela River, eight miles from Pittsburgh. Home to Andrew Carnegie’s first steel mill, in 1875, and first free library, Braddock has lost 90 percent of its population since World War II—and many of its grand old buildings to lack of maintenance and landlord absenteeism.

Older residents still remember having to fight the crowds to walk down the main street. Now Braddock is a predominantly African-American community of about 2,800 people with rampant unemployment and the highest poverty rate in Allegheny County. Some neighborhoods boast pockets of well-kept, often Victorian-style, houses, but the downtown strip holds mostly boarded-up buildings and weedy lots. There are a few bars, a convenience store and used-furniture store, and Hidy’s Café serves terrific burgers—but the Family Dollar store is the brightest presence. The town’s hospital closed down earlier this year. About 560 people work at Braddock’s last big employer, the original Edgar Thomson Steel Works, down from more than 5,000 in its heyday. Most of them don’t live in town. The blast furnace still runs 24-7, generating white smoke and a constant humming. “I know what living in Cambridge is like,” allows Fetterman, 41. “I would rather be here. It’s just where I feel like I belong.”

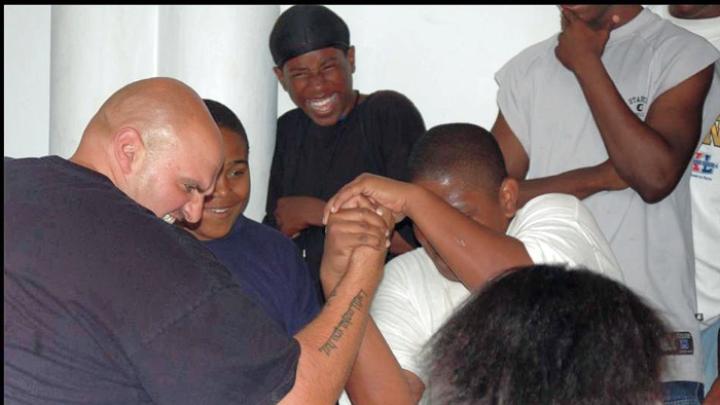

In 2001, feeling alienated from the dot-com revolution, Fetterman came to town to establish and run a county-sponsored program for school dropouts, which he set up from scratch. (He’d created and run a computer lab for young people in Pittsburgh in the 1990s.) The job suited his energy and resourcefulness, and he quickly built relationships with the 16- to 24-year-old crowd—helping them earn GEDs, get jobs, or find volunteer work, even mediating for them with families, social-service agencies, and the police. Four years later they helped vote him into office.

As mayor, Fetterman’s M.B.A. from the University of Connecticut has come in handy. But business alone leaves him cold. He has experienced social work, an abiding interest, as “calcified in terms of being able to do anything really interesting and adaptable,” he says. “It also wasn’t empowering to me, or the people in its system.”

He did enjoy the Kennedy School, getting the most out of ex-politicians on the faculty like Alan Simpson of Wyoming or Philip Sharp of Indiana, who now runs the think tank Resources for the Future. Taking the education and social-policy track, Fetterman focused at one point on analyzing a new program in Boston, “Technology Goes Home,” which handed out computers to school children—and tussled with the mayor’s office over the anticipated results. “People thought they’d be doing their homework and learning,” he says. “I said, ‘No, they’re going to be looking for lyrics and talking to their friends.’ I think that was borne out in the end.” But research and academic public policy were too removed from the daily lives of people he wanted to work with.

In braddock, Fetterman has managed to fuse what he likes best about these disciplines into a political role as social entrepreneur and “micro-philanthropist.” “Making significant improvements in and beating back what many would say is the inevitable decline and implosion of a post-industrial community—isn’t this why you go to a public-policy school?” he asks. “Don’t people in these jurisdictions deserve to live in an improving set of circumstances? It’s never going to be equal, but that doesn’t mean that people can’t be safe, have opportunities for their children—and not have to watch 90 percent of their town get carted off to the landfill.”

He is wholly engaged in a struggle to elevate this town and the lives of its tough-minded residents through his own brand of innovative, often improvised, urban renewal. “I dig this town’s malignant beauty, its people and its history,” he adds. “To me, this is a place that should be saved.”

So far, he has integrated the arts, the green economy, robust kids’ programs, and private and public capital in rehabilitating about half a dozen decrepit downtown buildings that he has bought and fixed up, primarily through his all-volunteer nonprofit 501(c)(3), Braddock Redux. He and a core group of supporters turned an old convent across from the Thomson plant into a barebones hostel for visitors. The adjacent former Catholic school is now the Unsmoked gallery, which has showcased artists from Pittsburgh and New York City and offers studios upstairs that rent for $100 a month. “What else would it be used for?” he explains. “The arts are good for any community and our art openings and events bring in all kinds of people who wouldn’t otherwise take an interest in what’s going on here.”

About two dozen new people, mostly artists, have moved into town, lured by Braddock’s primary marketable asset, cheap real estate: the average home costs about $6,200; a pristine home with a little land, about $25,000. But many were also drawn by the town’s faded industrial aesthetic and the chance to be urban homesteaders, community organizers, and participants in Fetterman’s vision, captured in a mandate—“Destruction breeds creation: create amidst destruction”—on his own Braddock-themed website, which utilizes the town’s zip code: www.15104.cc (which he also has tattooed on his forearm).

From Braddock’s ruins, he believes, something new can rise that balances what its residents need—jobs, services, commercial enterprises—with what newcomers can contribute. “Braddock isn’t and shouldn’t be turned into something Harvard Squarish; that’s not what we are,” he says. And it’s not a town for slackers. “You can’t come here and drink your Pabst Blue Ribbon and sit back and say ‘Reality bites,’” he asserts. “This place is irony-free. We need people who want to roll up their sleeves and work on improving the lives of everyone who lives here.”

Sometimes the cultural chasm pulls in seemingly opposite directions. On the Colbert Report last year, Fetterman made the case for a Subway fast-food shop to open in town. “I could hear the groans: ‘Why wouldn’t I want a funky vegan bistro instead?’” he says. “That’d be great, too. But I need something to fit with the needs and desires of the people who live and work here. Like big-box stores. I’d rather see local businesses, but people here do need a supermarket and where else can I get 300 hot dogs and 20 packs of buns for kids to eat at the fair this afternoon?”

Among his biggest projects has been transforming a former Presbyterian church, which he and his father bought for $50,000 in 2003, into a youth center. The center, named for Nya Page, a Braddock toddler sexually assaulted and left to freeze to death by her father, will soon open thanks in part to the more than $1 million Levi Strauss & Company pledged to Braddock Redux in a deal Fetterman brokered last year, when the company chose to build its 2010 advertising campaign, “Ready to Work,” around Braddock and its residents. (Townspeople were paid to star in print ads and commercials airing nationwide this past summer; “I did not get a penny personally from this deal,” Fetterman repeatedly points out. “Not even a free pair of jeans.”)

As Fetterman talks, three boys walk by, wearing Braddock Youth Project (BYP) T-shirts that group members designed and silk-screened themselves. The BYP was developed by Fetterman with one of his primary collaborators, the KEYS Service Corps, the local AmeriCorps unit. BYP teenagers work extensively on the expanding two-acre Grow Pittsburgh organic urban farm that has replaced trash-filled vacant lots along part of the main drag, Braddock Avenue. The boys are carrying watering cans and jokingly ask if the mayor wants his flowers drenched.

In 2003, for $2,000, Fetterman bought the abandoned furniture warehouse across the street from Carnegie’s majestic stone library and transformed it into an industrial-style loft home, using many parts salvaged from Braddock debris. (He and his wife, Gisele, have a toddler, Karl, and a dog named Kale.) In a hip twist, he put two old freight-car containers on the roof, now used for his wife’s closet, yoga practice area, and storage space. At his invitation, local graffiti artists decorated his home and yard during the renovation, so all the kids know where he lives: at the heart of their energy and activity—across from the library, next to the youth center, and a few doors down from well-used basketball courts he had built.

Fetterman himself grew up in York, across the state, a mid-sized, fairly prosperous place where he played offensive tackle for his high-school football team. His father, Karl, started and still runs a commercial insurance company. “Our family is comfortable, but we’re certainly not Rockefeller rich,” he says. “Gisele and I live very frugally.” The mayoral post pays $150 a month.

Fetterman is a politician, but more for the bully pulpit and authority to act than any personal vanity. But his daily work is entrepreneurial and essentially extra-governmental. Braddock Redux is a small, nimble entity able to make decisions and act quickly without being mired in a political process. He doesn’t have to write grants, for example, every time he wants to do something in town. “I have the financial freedom to say, ‘Hey, it’s 98 degrees out here and everyone’s sweating and unhappy. Let’s buy tickets on Fandango and take the kids to the movies this afternoon. Let’s just do it!’” Is the money going to run out? “So far, so good,” he says. “Levi’s has been good to us and my own family resources have been good. And I am not spending extravagant sums.”

He does have some critics. Not all the artists and newcomers have found him as supportive as they would like; some are overwhelmed as well by the work involved in being a change agent. Some large projects, like the renovation of the eight-story Ohringer Building, have had setbacks: the artist tenants were evicted in 2007, after which Braddock Redux bought the structure for $15,000. But last year Fetterman got a $100,000 Heinz Foundation grant to put up a green roof that kids in the BYP are helping create.

Politically, in Pennsylvania, the county is the most powerful and primary local governing body, but each borough within it has a local elected council. The mayor’s role, technically, is to monitor the police department—a job Fetterman generally leaves to the police chief, with whom he is on good terms. Some Braddock council members have criticized Fetterman for bringing negative attention to the town, and not knowing enough about the logistical aspects of town administration, while the borough manager, in an article in Rolling Stone, essentially said the mayor was “full of s…t” and accused him of wanting to create “Fettermanville.”

Fetterman says he feels empathy for the older people on the local borough council who “lived through the implosion of their town” and has tried to work with them, but they generally have “nothing constructive” to offer on how to improve conditions in Braddock. “I don’t want to get distracted with petty issues, old personal grudges, and quibbling,” he adds. “We know how that movie ends because that’s what’s happened in the past and that’s how Braddock got where it is.” He depends on what he considers a better working relationship with other local nonprofits working hard in Braddock before he arrived, with the county economic development team, and with the Democratic county executive, Dan Onorato (currently running for governor). In 2009, Fetterman was reelected by a margin of nearly three to one.

In his mind, it does not take much to improve people’s lives in little ways on a daily basis, while working on the more intractable problems, like bringing in employers. “We’re not ready to bring in Adobe Systems or Google, we are not at that level,” he says, “but there are things we can all agree on that are fundamental and doable now: opening playgrounds that are staffed for children; running a summer-jobs program that gives kids meaningful jobs.” He notes that KaBoom (a national nonprofit that creates play spaces where there are none) is installing a new playground this fall, down the hill from the youth center and his house, thanks to a matching grant offer from KaBoom. (He is paying $5,000 and the local Heritage Community Initiative is paying $2,500.) “I’m looking to do the most advanced things that are relatable to this community. Even though people thought it was strange to grow organic vegetables by the steel mill, it’s not such a radical concept that people are going to reject it.”

What’s next? “People say, ‘What’s your five-year plan?’ Well, I don’t have a five-year plan and I didn’t have one five years ago,” he says. “It’s not because I’m not organized or not thinking of the future. I just think that as long as you never forget the things that are really important and balance the needs in this community, then you are moving in the right direction.” At the Aspen Ideas Festival in July, where he spoke on three panels, he latched onto a new expression: Most Advanced Yet Most Acceptable. “This is what I’ve been doing intuitively,” he says. “It’s about what we can do for all the residents here that will resonate, while refraining from advancing some utopian version of progress that would fall flat on its face. Five years ago I never would’ve thought we’d even get this far.”