One evening in the fall of 2006, Sangu Delle and Darryl Finkton sat talking on the steps of Weld Hall. In Ghana, Delle, whose father works for the African Commission on Health and Human Rights Promoters, had grown up with firsthand awareness of human-rights abuses: he met refugees, sexual-assault victims, “people who had had limbs chopped off by warlords.” As a boy in Indianapolis, Finkton saw problems more common to American inner cities: drugs, gun violence, and absent fathers. They came from places half a world apart, but Delle and Finkton (now seniors and roommates in Quincy House) discovered they shared a response to the adversity they’d seen. “It taught us a lot about the resilience of the human spirit and the capacity to move forward in spite of it all,” says Delle.

A few weeks into their freshman year at Harvard, they felt a desire to help people who didn’t have access to such plentiful opportunities. They weren’t sure what they wanted to do; they just knew they wanted to do something. They gave themselves two years to get that something off the ground.

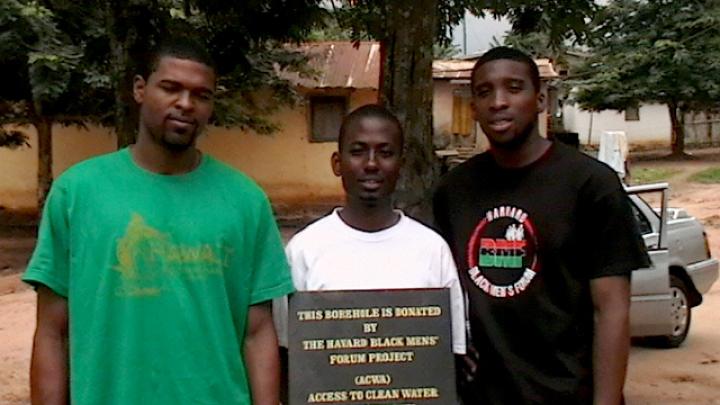

Project Access to Clean Water for Agyementi (ACWA)—serving Agyementi, a village 24 kilometers north of Accra, in Delle’s home country—has brought clean water to a population of 2,000 that previously used a water source designed for 300. Delle hopes this will be just a first step; they are also building latrines there, at the pace of 25 per year, and they hope future Harvard College students will carry on similar work through the Harvard African Development Initiative, a student group that has also applied for federal tax-exempt status.

The reason Delle and Finkton chose water and sanitation as their issues is simple: 1.6 billion people worldwide still lack these basic necessities. “It baffled us how we are able to send men to the moon but we cannot ensure access to clean water and sanitation,” says Delle.

They both enrolled in a Harvard course in Twi, the local language in Agyementi, so they would be able to conduct their own surveys and tests of water in people’s homes. (Delle spoke some Twi, but grew up speaking mainly other languages: Hausa, Dagaare, English, and French.) They cobbled together funding from sources including the Du Bois Institute, the Committee on African Studies, and the department of African and African American Studies, and raised substantial private donations as well with their “20-10” campaign (asking students to give $20 each and spread the word to nine friends). And in December 2007, they traveled to Ghana to meet with people from the government and non-governmental organizations (NGOs), sharing their ideas and asking for recommendations on “a community large enough to make an impact, but small enough to be feasible.” The minister of water proposed Agyementi.

The students’ initial idea included state-of-the-art water purification powered by solar energy. Nice idea, the minister of water told them, but would they come back to Ghana to repair the solar panels if they broke? They pared down their plans to something simpler and more easily repaired, in the process learning the importance of responding to local needs and—even more rudimentary—asking about local needs.

Back at Harvard, Delle, an African studies concentrator who after graduation is headed for the Harvard Business School "2+2" program, developed the project into an alternative thesis for that concentration’s new social-engagement initiative. Taking a truly multidisciplinary approach, he consulted not only his thesis adviser, professor of history and of African and African American studies Emmanuel Akyeampong, but also economist Michael Kremer; health economist David Cutler (now serving in the Obama administration); anthropologist Duana Fullwiley; and Allan Hill, a demographer at Harvard School of Public Health.

He also read roughly 200 academic journal articles on development topics, assigned by Akyeampong during an independent study. His work in Agyementi brought the articles’ arguments into sharp relief; his criticisms were based on experience, rather than the theoretical impressions of most student response papers. “You get to see how what you learn in the classroom is challenged by the cultural prescriptions of the communities you’re dealing with,” he says.

Delle spent last summer in Ghana and is also spending fall semester there; conveniently, Akyeampong is also there, on sabbatical. (Finkton, a neurobiology concentrator, was in Ghana in 2008 for the borehole construction, but spent last summer working in a lab in Paris.)

Delle was originally an economics concentrator, but switched to African studies after noticing that the most successful strategies in one community may not work well at all in another. “The flaw I saw in economics was that there aren’t data points for culture,” he says. “I can’t put cultural idiosyncrasies into my model, and they’re important.”

Nonetheless, he believes firmly in an entrepreneurial approach to development. After graduating, he hopes to merge lessons from Agyementi with what he has learned during summer internships at Bear Stearns and Goldman Sachs. “Instead of dollars being my returns,” he says, “I’m looking at life expectancy as my returns. If we apply entrepreneurial models to the nonprofit world, we’ll have things that work.”

He also believes in the power of creativity and even naïvete—of being too young and idealistic to listen to all the reasons why you shouldn’t try to solve a particular problem. “Students are not professional development workers,” he says. “We are generators of ideas. Because we are not corrupted by the limitations of the real world, we can imagine solutions.”