There was a time when Bill Scheft ’79 wrote fiction from 10 a.m. until noon in a windowless, five-by-five closet inside his spacious midtown Manhattan apartment. Then he’d walk a few blocks to the offices of the Late Show with David Letterman, where, since 1991, he has been a comedy writer, specializing in monologue jokes and Top Ten lists. One day his wife, Adrianne Tolsch, warned Scheft to wait longer before emerging onto the street: “You’re going to get hit by a cab,” she said. Scheft admits that writing fiction makes him “a little lightheaded. You sit down and try to get yourself into this state of mind--you are maneuvering in this world. You’ve got to sit there in the silence and let the answers come into the silence. You’ve got to stare into the abyss. It’s the antithesis of joke writing.”

Not that Scheft’s novels--the last three have been published--aren’t funny. After all, he was a standup comedian for 13 years, touring the United States, Canada, and Australia (“I was a good act, not a great act--Jews, sports, and weather”). His newest fictional effort, Everything Hurts, explores the world of mind-body medicine with Phil Camp, a protagonist so hobbled by lower-limb pain that he becomes a virtual agoraphobe and writes his wildly successful, nationally syndicated advice column flat on his back on a pad in his New York apartment. “To walk and sit and run and bend like any other neurotic forty-six-year-old had become his full-time job,” Scheft writes. “Phil’s part-time job was urinating. Fifteen times a day.”

Phil does leave his apartment and becomes a patient of a mind-body doctor whose hit book on pain is called The Power of Ow! The protagonist’s ordeal parallels certain experiences of the author. “I dragged a foot, limping, in constant pain, for four years,” Scheft relates. “I was told there was nothing wrong with me, it was psychogenic. I wrote this book to ‘art’ myself out of the pain. The guy in the book got better before I did. Ten days after I sold the book, I went to see another doctor, who took one look at my most recent x-rays and said, ‘You need a hip replacement.’ And that was it. But I do believe in psychosomatic theories; the pain is real, but the root of the pain is in the brain. I’m a big fan of the examined life--I’m in my third decade of psychotherapy.”

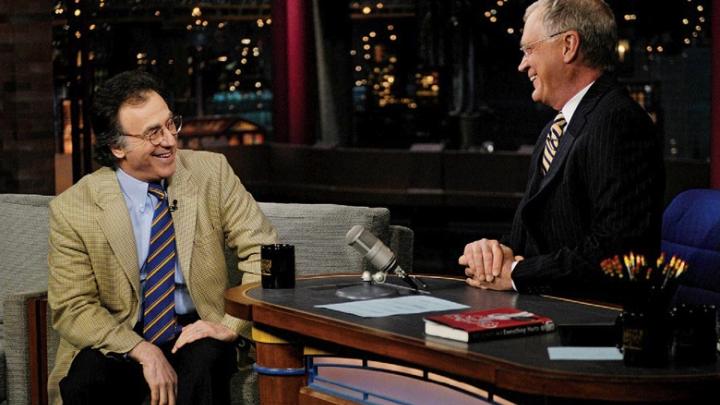

The Letterman job gives Scheft a “base, a place to go” that enables him to write his novels, a craft he began in 1995. The two forms of creativity are radically different. “Writing monologues, that’s a volume business. You’re making mounds and mounds of coleslaw and trying to get one nice helping,” Scheft explains. “And you are using more of your quick-twitch muscles. As Woody Allen said, ‘If you can do it, there’s nothing to it.’ It’s formula--the setup and punch line and the glue between them.” Writing full-time for Letterman means cranking out 50 or 60 jokes per day. “Dave will check 10 to go on cue cards, and use five,” says Scheft. “And that’s a good day. Dave’s voice is always in my head; he’s the smartest guy, and the best writer, in the room.”

Scheft grew up in the Boston area, the fifth of six children. “Growing up in a large Jewish family, there’s never enough guilt to go around,” he explains. One of his uncles was Herbert Warren Wind, long a fixture at the New Yorker and author of several books on golf and one on tennis. “He had the biggest influence on me of any man,” says Scheft. “Uncle Herb was so generous, showing me the possibilities of the writer’s life. If I think of myself as a writer, he is something else.” The Ringer, Scheft’s first published novel, has a character based on Wind--an elderly writer whose nephew makes a living as a hired athlete (a “ringer”) for restaurant and corporate softball teams in New York City.

During the 1980s, Scheft himself made some cash doing exactly that; an outfielder, he had played a little baseball at Harvard, though he switched to Crimson sportswriting when he was cut from the team. He concentrated in classics, having fallen in love with Greek and Latin (“I thought the Church was going to come back”) at Deerfield Academy.

After college, he continued sportswriting for two years at the Albany Times-Union, but soon moved to New York City and began performing standup at the renowned comedy club Catch a Rising Star. (He’d done standup a few times at Harvard, and once won a talent show at Quincy House.) He succeeded Bill Maher there as a house emcee, a slot Scheft held from 1982 until 1987. “I was really lucky to get into standup just as the comedy boom started,” he recalls. “Clubs were opening up all over.” He performed on the road 30 weeks a year, and did “every TV show except the two that could actually help your career--Tonight and Letterman.”

Scheft had always wanted to write for television but couldn’t get such a job “because of a decision I’d made at age 18, to go for the Crimson, instead of the Lampoon.” Eventually he ran into Letterman’s executive producer while eating lunch at the Friars Club and submitted some jokes; the first one to air was, “Liz Taylor and Larry Fortensky had their first fight, over whether he should unpack.”

Eighteen years later, he’s still there, minus a couple of leaves to write books. He still enjoys comedy writing and calls it a job that’s about “service.” In his mind, though, Scheft didn’t consider himself truly a writer until The Ringer appeared in print in 2002. “When you get a novel published,” he says, “you have to admit you’re a real writer.”