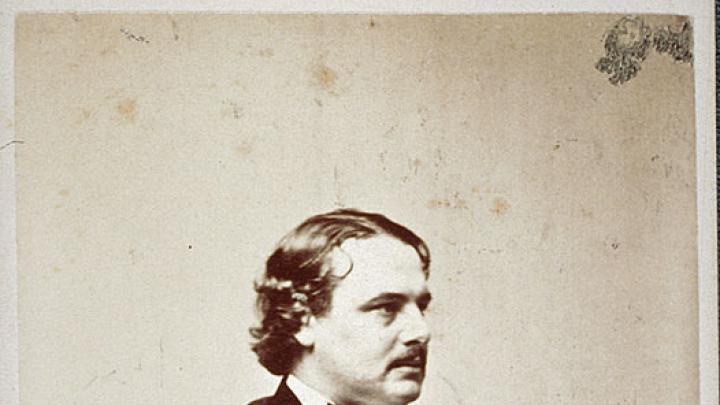

Within months of his 1857 inauguration, President James Buchanan plunged nearly a third of the U.S. army into an unprecedented power struggle with Utah territory’s pugnacious governor, Brigham Young, and his large Mormon militia. Traveling with the army was Albert Gallatin Browne Jr., A.B. 1853, a 25-year-old war correspondent for Horace Greeley’s New York Tribune—who also talked himself into the job of clerk for Utah’s new federal chief justice, Delana R. Eckels, en route.

Browne’s path to the Utah War (1857-1858) was anything but straight. The son of a prominent Salem, Massachusetts, ship chandler and abolitionist, he chose to forgo his father’s business to enroll at Harvard Law School and study with Boston lawyer and abolitionist John A. Andrew. In 1854 he helped lead the mob seeking to free escaped slave Anthony Burns from federal officers enforcing the Fugitive Slave Act; when a constable died, Browne and several of Boston’s most prominent abolitionists were indicted for homicide. The charges were dismissed, but Browne’s family packed him off to the University of Heidelberg to take a Ph.D.—a distinction that prompted illiterate mountain man Jim Bridger to dub him “Doc” when they shared an army bivouac in the Rockies.

How Horace Greeley came to hire fellow-abolitionist Browne as a reporter is unclear; Browne’s acceptance is not. By 1855, he had already considered a well-paid job as European correspondent for another newspaper. Once home, in 1856, he told an acquaintance he was resuming legal studies, but added: “I must learn to love the law from necessity, for I cannot from choice.” The risky Tribune assignment offered an alternative—and was sufficiently noteworthy that a Mormon agent on the East Coast reported it to Brigham Young. Thus began Browne’s second career, in journalism and publishing.

Key to Browne’s success as a war correspondent were his curiosity, energy, resourcefulness in cultivating knowledgeable sources (military and civilian), and extraordinary access (through Judge Eckels) to newsworthy court documents, such as Young’s federal treason indictment. So fascinating were his dispatches that one infantry officer in the expeditionary force had a friend in Buffalo mail him the Tribune so he could read Browne’s reports on gossip from other regiments. Along with garrison tidbits, Browne included his own strong opinions: after Young proclaimed martial law and Mormon raiders destroyed nearly $1 million in army supplies, he wrote, “Either the laws of the United States are to be subverted and its territory appropriated by a gang of traitorous lechers, who have declared themselves to constitute ‘a free and independent state,’ or Salt Lake City must be entered at the point of a bayonet, and the ringleaders of the Mormon rebellion seized and hung.” Technological advances in printing and telegraphy meant that his Tribune articles were relayed to the mass readership of other newspapers throughout the country. His copy reflected the style of the earliest English war correspondents covering the recent Crimean War and provided a model for reporters in the coming Civil War.

Then Browne himself became part of the story. On New Year’s Day 1858, the Utah expedition’s commander, having learned of Mormon plans for a spring offensive, offered him an extraordinary mission: return east with a plea to Buchanan and the army’s general in chief for reinforcements. Four days later, Browne embarked on a daunting 4,000-mile trek to Washington and back that ended at the expedition’s winter quarters at Fort Bridger, Wyoming, on May 28. When Young realized he was cornered, negotiations resolved the conflict: the Mormon leader was replaced as governor, a presidential amnesty for Utah’s entire population ended plans for 30,000 Mormons to flee the territory, and the nation’s largest army garrison was established near Salt Lake City. Browne stayed on until 1859, to file colorful descriptions of Mormon life and army frustrations, run unsuccessfully for the territorial legislature, and serve briefly as court-appointed guardian for a 12-year-old English girl whom the British government wanted repatriated after her retrieval from her aunt’s polygamous family. (He later published a thinly disguised account of the affair, The Ward of the Three Guardians.)

Back in Boston, he rejoined Andrew’s law office, lectured on Mormonism, and drafted the definitive insider’s account of the Utah War for the Atlantic Monthly. Then came Andrew’s election as governor in 1860, and the outbreak of the Civil War. Browne agreed to serve as Andrew’s military secretary, his confidante and expediter: the liaison between Abraham Lincoln’s principal gubernatorial backer and the government in Washington. After the war, he married a leading abolitionist and feminist, Martha “Mattie” Griffith, and worked successively as publisher for the Massachusetts federal court system and as editor of several New York papers, including the New York Herald, before returning to Boston to finish his life as a banker, clubman, and leader of his Harvard class. A classmate attributed his relatively early death to “a disease dating probably from the privations encountered in the Utah Expedition, from which he had suffered for many years with fortitude.”

The greatest adventures of Browne’s life were the Utah and Civil Wars. As the sesquicentennial of the first concludes and that of the second approaches amid continuing debate on media coverage of current wars, it is worth taking note of his foundational role.