The social status of physicians rose in the eighteenth century as their understanding of disease grew apace. But effective new treatments or procedures would not follow for many years, and so doctorsbleeding and purging, as everbecame easy targets for satirists. Thus, as the consultation of physicians at left attempts an amputation, caricaturist Thomas Rowlandson suggests his opinion of the profession in a notice pinned to the wall behind them. A List of Examined and Approved Surgeons, it names such worthies as Sir Dreary DropsicalDavid PukeSir Valiant VeneryAbraham AbcessCristopher Cutgutt.

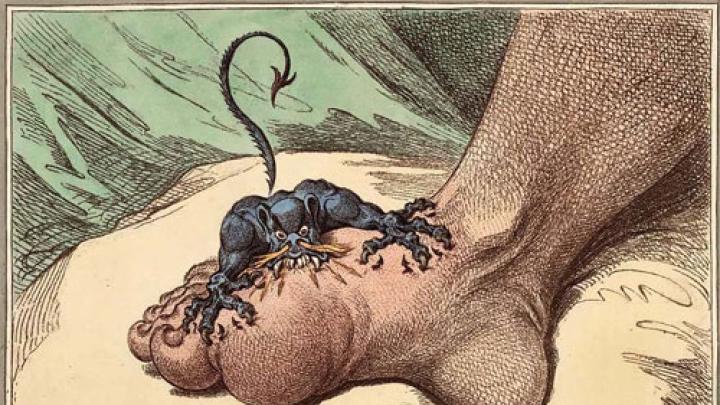

Because all their illustration tended to be allegorical and symbolical, the graphic satirists of the day often depicted common ailments as metaphors for societys larger social and political ills. See, for example, James Gillrays portrayal of gout, a form of arthritis frequently associated with high livingthe disease of kings.

The prints reproduced here are part of The Language of the Age: Depictions of Medicine in Graphic Satire (on-line at www.countway.med.harvard.edu/rarebooks/exhibits.shtml), a virtual exhibition of works from Harvards Countway Library of Medicine. They mock physicians and evoke the bodys ills, but satirists such as Rowlandson and Gillray by no means restricted their fire to such matters. Introducing the exhibition, the curators at the librarys Center for the History of Medicine write of the period: Rapid and significant changes in politics, economics, social structure, religious values, and scientific knowledge created uncertainty and anxiety among the public. The emerging managerial and professional classes that included politicians, lawyers, artists, academics, scientists and physicians rose in power and status, and became targets of public disquiet. Graphic satire was one means of expressing social anxiety that allowed criticism of the emerging elite.

![]() The public were avid buyers of these radical, disruptive, propagandistic, sometimes libelous, often hilarious prints, wrote the late M. Dorothy George, coauthor of Catalogue of Political and Personal Satires in the British Museum (which has a vast collection of them). Satire was the language of the age, she observed. In the eighteenth century there was a great vogue for satirical printspolitical and social. This was the golden age of the English engraver. Their prints were virtually the only pictorial rendering of the flow of events, moods and fashions. Especially, they reflect the social attitudes of the day.

The public were avid buyers of these radical, disruptive, propagandistic, sometimes libelous, often hilarious prints, wrote the late M. Dorothy George, coauthor of Catalogue of Political and Personal Satires in the British Museum (which has a vast collection of them). Satire was the language of the age, she observed. In the eighteenth century there was a great vogue for satirical printspolitical and social. This was the golden age of the English engraver. Their prints were virtually the only pictorial rendering of the flow of events, moods and fashions. Especially, they reflect the social attitudes of the day.

~Christopher Reed

Metallic-Tractors courtesy of the Boston Medical Library/Francis A. Countway Library of Medicine; all other images courtesy of the Harvard Medical Library/Francis A. Countway Library of Medicine.

Metallic-Tractors, 1801, by James Gillray. A physician deploys a device invented by Dr. Elisha Perkins of Connecticut and claimed to cure disease through electric force. Gillray was skeptical. The newspaper on the table reads in part: Just arrived from America, the Rod of sculapios, Perkinism in all its Glory being a certain Cure for all Disorders: Red Noses, Gouty Toes, Windy Bowels, Broken Legs, Hump Backs.

Amputation, by Thomas Rowlandson, 1785.

Ague & Fever, 1792, by Rowlandson. Ague, the snake, brings shivers, while Fever stands waiting and a doctor writes a prescription. A line from Milton at the bottom reads: And fed by turns the bitter change of fierce extremes, extremes by change more fierce.

The Gout, 1799, by Gillray. A full-time caricaturist, Gillray (1757-1815) created more than 1,500 works, many political. His favorite victims were George III and Napoleon. It is usual to think of Gillray, wrote British historian Dorothy George, as the most savagely uninhibited of English caricaturists. He slipped into madness at the end of his life and was cared for by his publisher, Miss Hanna Humphrey.

Thomas Rowlandsons 1810 peek at Dropsy Courting Consumption. Herakles, of classical proportions, is at rear. Rowlandson (1756-1827) began his career as a portrait painter and later illustrated novels. When he received a substantial bequest from an aunt, he embraced Londons lush life and sat at the gaming tables until his money left him. With the inspiration of his friend Gillray, he then looked to caricature to make his living, commenting with gusto on human weakness.

A Sore Throat, 1827, by H. Pyall. Egad its worse & worse, reads the subtitle.

Artist George Cruikshank visits a self-medicating sufferer, at home with her range of animals, in Mixing a Recipe for Corns, 1819.

Cruikshanks The Blue Devils!!, 1835, bring torment to the mind. The devil clinging to the mantelpiece offers the sufferer a razor.

More Cruikshank devils engineer an attack of Cholic, first published in 1819 but recurring as part of a set of prints in 1835. Cruikshank (1792-1878), from a family of caricaturists, satirized both Tories and Whigs with zestful irreverence as a young man, but went on to display a more genial side as an illustrator of some 850 books, including novels by Dickens and numerous childrens books. In the 1840s, he became a propagandist for temperance.

The Cowpock, 1802, by James Gillray. Dr. Edward Jenner used cowpox to vaccinate against smallpox. Gillray shows the result: immediately upon being vaccinated, Jenners patients sprout cows. In this instance the satirists disdain was misplaced; Jenner was on to something.